Hume’s Empiricism

David Hume (1711-1776) was a Scottish philosopher who is now universally considered preeminent among the so-called “British empiricists.” However, even higher praise comes from Kant himself, who said that Hume “awakened me from my dogmatic slumber.”

“Dogmatic” in Kant’s time referred specifically to the “rationalism” of Descartes and his followers. This rationalism claimed that only “pure” ideas (in the Platonic sense) could penetrate into the true nature of things, because empirical ideas were too fundamentally unreliable a foundation upon which to ground metaphysics. So, “dogmatism” differentiated between “appearances” (empirical ideas) and “reality” (what can be known strictly through analysis, what Plato called “dialectic”).

Kant was extremely impressed with the systematic, rigorous arguments put forth by Hume to demonstrate that only empirical ideas can be truly about the world (doing metaphysics), while “pure” ideas can only be “relations of ideas” and never tell us anything about the world. (We will return to these critical points shortly.)

So, pre-Hume, Kant was a “dogmatic” rationalist. However, prompted by Hume’s arguments, Kant completely rethought the entire basis of metaphysics.

The extremely high regard with which Kant is held goes back to Hume, as Hume changed the entire perspective and philosophical direction of the mighty Kant.

However, Hume deserves attention in his own right, as he did the most rigorous job of explicating empiricism that has ever been done in human history. It is sadly ironic that Hume was not widely taken seriously in his lifetime. He even wryly joked that his three-volume Treatise of Human Nature “fell still-born from the press.” However, in the centuries since Kant pointed back to Hume’s profound influence, Hume has been granted the acclaim for genius that he would have found satisfying during his life.

We will focus upon his small masterwork, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, renamed and republished in its final form in 1758. Hume famously told a critic that the Enquiry must “alone be regarded as containing my philosophical sentiments and principles.” This volume, though much shorter than his earlier Treatise of Human Nature, is a much more worked-out, mature, and concise exposition of the ideas he had been working on for decades. In this small volume can indeed be found the most elegant, thoroughgoing “treatise” on empirical metaphysics ever produced.

In the Enquiry, Hume recognizes a number of subtle distinctions previous philosophers had overlooked, and he then worked out the implications of these distinctions to demonstrate what empiricism really is all about.

Analytic vs. Synthetic

Here we employ Kant’s terms for Hume’s distinction, although Kant actually sharpens Hume’s ideas considerably. Hume’s terminology is more cumbersome, and we are headed toward Kant anyway.

Hume argued that we have two sorts of knowledge: 1) what he called “relations of ideas” (which Kant calls “analytic”), and 2) “matters of fact” (which Kant calls “synthetic”). To plunge into the distinction, we first need to understand Hume’s pillar principle of empiricism:

All simple ideas arise from antecedent (prior in time) simple impressions.

So, empiricism really is the principle that all of our ideas derive from sensory impressions that the world makes upon us. There is no content of our thinking that is not dependent upon earlier sensory impressions.

Hume distinguishes between “simple” ideas and composite ideas. For example, let’s say that you have an idea of a unicorn. Nobody got that idea from having an impression of a whole unicorn, because people have never seen a whole unicorn. Instead, people have seen horns and horses and narwhals and so forth. So, people have had “simple” impressions of long, spiraled horns. They have then put such ideas together with other composite ideas, such as of a horse, and their imaginations have thus produced a composite idea of a unicorn that is really based upon a whole array of composite ideas. This is how real, but simple, impressions/ideas can be combined into complex, composite ideas, including composite ideas of entirely imaginary entities. And the ideas we have of imaginary objects and creatures is why Hume says that all simple ideas arise from antecedent simple impressions.

So, for Hume, all simple ideas are grounded in “reality,” although what he means is the “reality” of our sensory impressions. We really do have sensory impressions, and these are the basis of all of our simple ideas.

Now, you can “group up” simple ideas in two ways, which is the basis of Hume’s foremost distinction:

1) You can have “matters of fact” knowledge in subject/predicate form.

2) You can have “relations of ideas” knowledge in subject/predicate form.

Both Hume and Kant made what we now recognize to be an oversimplification in calling all complex ideas subject/predicate complexes. So, let’s consider several examples to help sort out this distinction.

My dog, Thor, is black. “My dog, Thor” is the subject; “black” is the predicate; and this example is a “matter of fact” sort of knowledge. I can only know whether it is true or false by experience, so its truth conditions are empirical.

Bachelors are unmarried men. “Bachelors” is the subject; “unmarried men” is the predicate; and this is a “relations of ideas” sort of knowledge. Such “analytic” statements are true by definition and false by contradiction. Empirical knowledge does not contribute to their truth or falsity. For such knowledge, its truth conditions are “internal” to the statements themselves; you don’t have to have sensory experience to know the truth or falsity of “relations of ideas.”

1 + 1 = 2 This does not neatly fit into subject/predicate form; Hume would call this a “relation of ideas,” while Kant would call it “synthetic,” so this is an example in which Kant argues that Hume is mistaken about the “analytic” nature of this knowledge. But what sort of knowledge is this, if it is not in subject/predicate form?

Hume called all logical and mathematical relations “relations of ideas,” while Kant later argued conclusively that they were not analytic “relations of ideas” but were instead “synthetic,” but not “matters of fact.” When we turn our attention directly to Kant, we will further explain how Kant sharpens up Hume’s distinction and uses it with incredibly powerful results.

Note that for both Hume and Kant, the subject/predicate form is a stumbling block when it comes to logical and mathematical ideas, because these relations are not properly expressed as a subject term that has properties! It is not that, say, 2 has the property of 1 + 1. If we say, “1 + 1 is 2,” the “is” we are using there is not the “is” of predication; it is the “is” of equivalency.

For our present purposes, we will leave aside the problem that not every proposition can be cast in subject/predicate form. I only mention the problem here because when we talk about Kant we will return to an implication of it that does matter. For now, however, just pretend that the subject/predicate form of expressing propositions is universal.

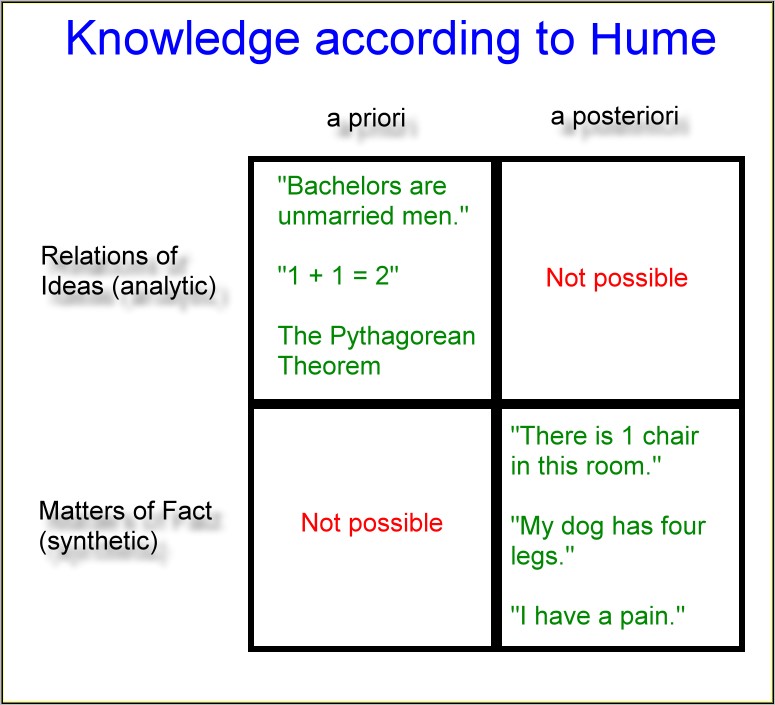

Now, we already know what the terms a priori and a posteriori mean. Right? Remember the “prior” and “post” aspects of the terms? So, a priori knowledge is that knowledge that is logically prior to experience, knowledge that cannot arise from experience. And a posteriori knowledge is empirical knowledge, knowledge that is logically dependent upon experience and that cannot arise apart from experience. With these two terms, coupled with the analytic/synthetic distinction, we can now present a “knowledge grid” according to Hume, and this will be all we need to get off the ground at present (click on the image to expand it).

Notice first that some combinations are impossible, according to Hume. They do not make sense.

Let’s take, for example, a posteriori analytic knowledge. We know that a posteriori knowledge is knowledge that must be gained from experience. But, by contrast, analytic propositions are true by definition and false by contradiction; we don’t need to know anything about the real world to know the truth or falsity of analytic propositions. The claim, “Bachelors are unmarried men” is true by definition; in fact, that proposition really is defining what the term “bachelor” means. There might be no such thing as a bachelor in the real world. There might be no such institution as marriage. There might be no men. And to discover the truth of that proposition, I cannot in principle do it by experience! I cannot go around to every man and “poll” to find out his marital status. And I cannot be certain the any given man I “poll” is not lying about his status. In short, empirical knowledge cannot contribute in any way to the truth of the proposition. So, analytic propositions have strictly a priori truth conditions, never empirical!

Next, let’s consider a priori synthetic knowledge. Hume argues that this form of knowledge is also impossible. Hume says that a priori propositions are not about the world in any sense. Their truth value could not be a matter of experience (because they are a priori), so they could not be telling us any “matter of fact” about the world.

If you want to know anything about the world, then you are dealing with “matters of fact” propositions. But those can only emerge from real-world experience, so they must be a posteriori.

If you are manipulating relations of ideas, then you are not beholden to the real world, nor are you making any metaphysical claims. Even regarding something like the Pythagorean Theorem, Hume argues that “Propositions of this kind are discoverable by the mere operation of thought, without dependence on what is any where existent in the universe. Though there never were a circle or triangle in nature, the truths, demonstrated by Euclid, would for ever retain their certainty and evidence” (Enquiry, p.15).

Remember that the “dogmatic” rationalists believed that you could only do reliable metaphysics by contemplating “pure” ideas that did not emerge from the senses, because “the senses are unreliable.” Hume is making the exact opposite claim about metaphysics: You cannot do any metaphysics by appeal to “relations of ideas,” because these tell you nothing about the real world. Instead, you can only do metaphysics by appeal to real-world ideas, and these are all “matters of fact” and emerge only from sensory experience.

So, for Hume, there are only two sorts of knowledge: a posteriori (empirical) synthetic, and a priori analytic. The former are about the world, their truth values are discovered strictly through experience, they are uncertain, and they are unreliable. The latter are not about the world but are merely about manipulating ideas, their truth-values are not discovered from experience, they are certain, and they are demonstrable.

Married-bachelors and spherical-cubes are contractions in terms, and we don’t need to know anything about the world in order to know that neither can exist. The truth conditions of “relations of ideas” are not in the world.

By contrast, unicorns are a possible “matter of fact” synthesis of ideas, so unicorns might exist; the only way to find out is to go searching the world for one. The truth conditions of “matters of fact” are necessarily in the world.

A final thing to note in this section is that empiricists are unwavering in their claim that all simple ideas arise from antecedent sensory impressions. And that means that all ideas (no matter how complicated and profound) ultimately emerged from simpler ideas that ultimately emerged from antecedent simple sensory impressions. This is literally what it means to be an empiricist and to believe that all knowledge is ultimately empirical knowledge.

How can this perspective work for such things as the emergence of Pythagorean Theorem? The calculations involving really large numbers? All of logic? And so on.

I have asked this question of several physicists I know, and they provide the same answer that Hume would: “We experience some single thing, and we grasp the notion of 1 from that unity of experience. We then discover two of the same thing, recognize the group as one such unity coupled with another such unity, and the principle of addition emerges. From there, manipulations of really large numbers are nothing but ‘addition writ large,’ and most of us can’t handle such complexity entirely in our heads. So, we invented calculators and computers to ‘keep in mind’ and perform these really large manipulations for us. But ‘relations of ideas’ they indeed are! Same thing with the Pythagorean Theorem. We experienced a line and then imagined a ‘perfect’ one with only length, no width. We experienced angles and started imagining all sorts of angles relating perfect lines. Then we started manipulating the relations between these ideas, and geometry emerged. All of it, just as Hume says, rests upon antecedent simple impressions. And from those emerging simple ideas, our imaginations performed the rest as true ‘relations of ideas.'”

There are, of course, profound problems with this account of such things as geometry, mathematics, logic, and Kant would say even morality. But we will get to those problems as we get deeper into Kantian metaphysics and how it accounts for experience in the first place.

For now, let us summarize that for true, consistent empiricists, there are only two forms of knowledge: a priori (which can also be called “relations of ideas” and “analytic”), and a posteriori (which can also be called “empirical,” “matters of fact,” and “synthetic”). A priori knowledge is not about the world, although the “simple” parts of the complex ideas that form it emerged from antecedent sensory experiences. By contrast, a posteriori knowledge is about the world, it’s truth conditions inhere in the world, and it is the only sort of knowledge that metaphysics can employ.